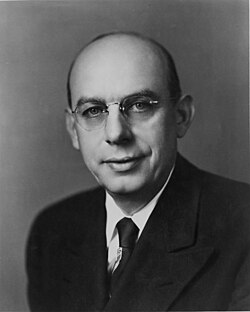

Today Florida is seen as a Republican stronghold, but back in 1962 its voters were loyal to the Democratic Party as a matter of tradition. However, this applied to the state, rather than national Democratic Party which was too liberal for many Floridians. Indeed, Florida voters at that time had thrice in a row rejected the Democratic nominee for president, yet the only Republican they had elected to Congress in the 20th century up to this point was Bill Cramer of St. Petersburg. Republican Edward John Gurney (1914-1996) was well-suited for this environment. He was a war hero who had been severely injured by German machine gun fire, and after earning his law degree he moved to Florida as the warm climate was better for managing the pain of his war wounds as opposed to his home state of Maine. His injuries produced a permanent limp and a lifelong issue with back pain. His fast rise in Florida politics, his personality, and his good looks helped him win by three points in a newly created district. Gurney proved to have staying power and was considered the most conservative member of the Florida delegation; indeed he got nothing wrong per the standards of Americans for Constitutional Action in 1963 and 1964. Gurney also voted against the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Although he was a strong opponent of the Great Society, he bent to vote for the Social Security Act Amendments in 1965, which had Medicare as its centerpiece given Florida’s high population of retirees. After his reelection in 1966, Gurney had his eyes set on the Senate, and with incumbent George Smathers not running again, he got an early start by fundraising in 1967, which helped get him a nearly 12 point victory over former Governor LeRoy Collins. This was in addition to Nixon being popular in Florida and Collins had a liberal reputation on civil rights.

While moving along in his career, Gurney suffered some tragedies. In 1968, his only son, Edward III, committed suicide and in March 1970 his wife Natalie suffered a severe stroke that resulted in her being bedridden until her death in a nursing home eight years later. While in the Senate, Gurney could be counted as a reliable supporter of the Nixon Administration, including a few occasions in which Nixon went against what conservatives wanted, such as voting for bailing out Lockheed Martin in 1971 and revenue sharing in 1972. His record on civil rights also differed a bit in the Senate from the House. Although he supported curbs on busing, he also supported extending the Voting Rights Act for five years in 1970 and supported strengthening enforcement of anti-discrimination laws. Both stances ran contrary to how he had voted while in the House. In 1970, Gurney was involved in party infighting when he sided with Governor Claude Kirk over Congressman Bill Cramer. Cramer wanted to win the Republican nomination for the Senate, while Kirk was backing G. Harrold Carswell, who was Nixon’s second defeated nominee for the Supreme Court. Congressman Cramer won the nomination, but lost the election to Lawton Chiles.

Watergate and Downfall

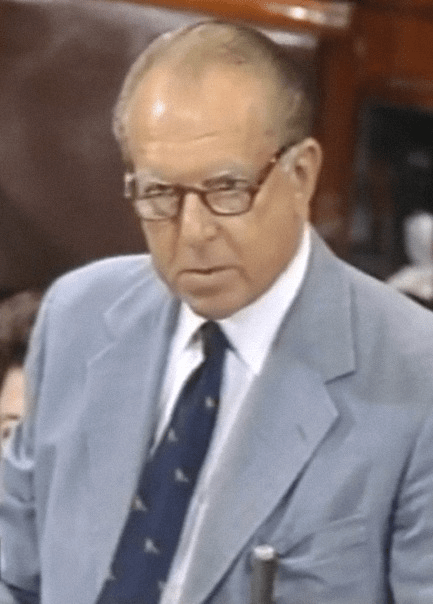

In 1973, Gurney was tapped to serve on the Senate Watergate Committee and he was President Nixon’s chief defender. It was his accusing Senator Sam Ervin (D-N.C.) of harassing witnesses with his line of questioning that resulted in him responding with his famous, “I’m just an old country lawyer, and I don’t know the finer ways to do it. I just have to do it my own way” (UPI). Gurney also notably grilled witness John Dean. Although Gurney looked well set for another term in the Senate, there was a serious problem: a major fundraiser, Larry Williams, had been pledging public housing contract awards to prominent Florida contractors in exchange for hefty contributions to the Gurney campaign and on January 17, 1974, he was indicted for accepting $10,000 from a Miami builder in exchange for favorable treatment by the Federal Housing Administration following an investigation by a grand jury into allegations that he had raised $300,000 from 1971 to 1972 in exchange for favors to contractors (The New York Times, 1974). The political blowback from this growing scandal may have motivated Gurney’s vote for the Federal Election Campaign Act Amendments in 1974, which he had cast right after voting for Senator James Allen’s (D-Ala.) motion to kill the bill. On May 13, 1974, Gurney testified to a grand jury under oath that he had not known about Williams’ secret fund-raising activities until June 1972 and had not known about their illegality under summer 1973 when he had requested a Justice Department investigation (The New York Times, 1975).

On July 10, 1974, Gurney himself was indicted by a Federal grand jury on seven felony counts in Jacksonville, four of which were for making false statements in his testimony and promptly dropped his reelection campaign. He only sided with the liberal Americans for Democratic Action 3% of the time in his time in Congress, the conservative Americans for Constitutional Action 92% of the time, and his DW-Nominate score was, rather surprisingly given these scores, a 0.306. His trial hinged on, much like President Nixon and Watergate, what did Gurney know and when did he know it?

In June 1975, things appeared bad for him when his administrative assistant, James Groot, pled guilty to conspiracy and provided testimony for the prosecution that contradicted Gurney’s testimony. Numerous contractors testified against Gurney and his co-defendants, while Senators James B. Allen (D-Ala.), Jesse Helms (R-N.C.), and Clifford Hansen (R-Wyo.) were character witnesses for Gurney. On August 6th, he was acquitted of five of the seven charges with the jury deadlocking on the other two; jurors voted 9-3 for conviction on the conspiracy charge and 7-5 for acquittal on making false statements to a grand jury. In September 1976, the prosecution dropped the conspiracy charge for lack of evidence and on October 27th, he was acquitted of perjury. Gurney said after the trial, “They destroyed a United States Senator, blackened my name and besmirched my character” and held that the Justice Department had moved against him based “on flimsy evidence gotten from plea-bargainers” (The New York Times, 1976). Although Gurney avoided prison, four people who worked on his campaigns went to prison for their illegal fundraising methods. Gurney’s media aide, Pete Barr, said of the matter, “A little of him died back then. The guy was a straight arrow. That was the sad thing about the charges against him” (Tampa Bay Times).

Getting Back in the Game

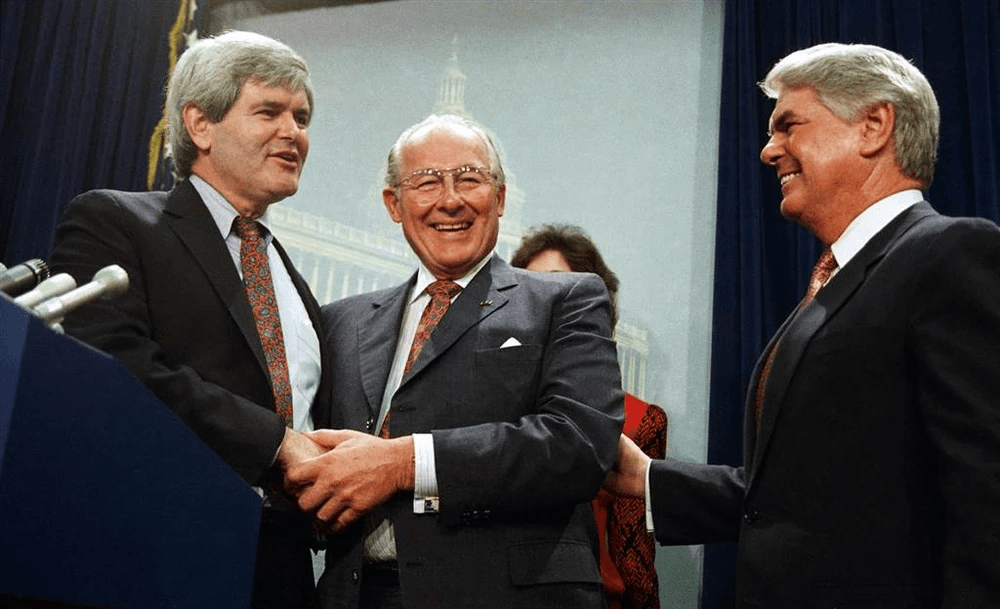

After Natalie Gurney’s death on January 3, 1978, he decided it was time to make a comeback. His successor to Congress, Republican Lou Frey, was not going for another term and the district could elect a Republican yet again. The 1978 race was one of contrasts; Gurney was 64 and running as an experienced, seasoned leader, while Democrat Bill Nelson was 35 and running on being a “fresh face with a clean record” (Peterson). At the time, Nelson was running as a conservative Democrat, taking the wind out of the sails of Gurney potentially trying to tag him as a “liberal”. Gurney also hoped that this race would add to his vindication and said, “You wonder [why] I’m bitter? They destroyed my career” (Peterson). This was in truth his last chance to get back in the game, do or die. However, even in 1978, the Democrats held a 60-40 voter registration advantage in the district, and the voters delivered a verdict that pretty closely reflected this advantage, Nelson winning by 23 points. Gurney did not seek public office again, remarried, and sold stocks and real estate for the remainder of his life. He died in obscurity on May 14, 1996, from what his friends reported was cancer.

References

ADA Voting Records. Americans for Democratic Action.

Retrieved from

Ex-Sen. Edward Gurney Dies in Obscurity. (1996, May 22). Tampa Bay Times.

Retrieved from

https://www.tampabay.com/archive/1996/05/22/ex-sen-edward-gurney-dies-in-obscurity/

Former Aide Disputes Gurney; Says Senator Knew of ’72 Deals. (1975, June 10). The New York Times.

Retrieved from

Fund-Raiser for Gurney Indicted in Pay-Off Case. (1974, January 18). The New York Times.

Retrieved from

Gurney Cleared of Five Charges at Florida Trial. (1975, August 7). The New York Times.

Retrieved from

Gurney, Edward John. Voteview.

Retrieved from

https://voteview.com/person/10593/edward-john-gurney

Judge Clears Gurney on One of Two Counts. (1976, October 26). The New York Times.

Retrieved from

Peterson, B. (1978, September 11). Florida’s Ex-Sen. Gurney Striving to Return to Congress. The Washington Post.

Retrieved from

Sam Ervin enjoyed telling those who asked about his… (1985, April 23). UPI Archives.

Retrieved from

Senator Gurney Fights to Clear his Name. United States District Court Middle District of Florida.

Retrieved from

https://www.flmd.uscourts.gov/senator-ed-gurney-fights-clear-his-name

The Hearings: Dean’s Case Against the President. (1973, July 9). Time Magazine.

Retrieved from

https://time.com/archive/6841330/the-hearings-deans-case-against-the-president/

Waldron, M. (1975, April 26). Gurney Trial Told of a Secret Drive. The New York Times.

Retrieved from